-

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

© BMW

© BMW -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

©

© -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

©

© -

©

© -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

© ohme

© ohme -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

©

© -

© Haymarket Media

© Haymarket Media -

©

©

-

The electrification of the car industry has brought with it a host of new words and terms for drivers to learn – and some of them can be rather confusing.

From charger types, to new systems like regenerative braking, there are a lot of challenging terms to understand.

With this in mind, we've put together a jargon buster of all the important key terms to help you embrace the thriving world of electric cars.

-

Electric Vehicle (EV)

We'll start with an easy one: EV stands for electric vehicle, obviously.

But there is a bit of a catch that can get confusing. While most people would class an EV as a fully electric vehicle, some people use the acronym to refer to electrified vehicles, which includes cars like plug-in hybrids that combine an electric motor and petrol engine.

-

Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV)

Since the EV acronym isn't always precise enough, you can be more specific by saying BEV (usually pronounced B-E-V). It stands for Battery Electric Vehicle, referring to cars that run purely on electricity.

BEVs can be charged using a household plug (albeit at a snails pace), a dedicated home charging point, or a public charger which can vary in speed.

-

Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV)

PHEV refers to Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles, which combine both combustion engines and a small electric motor. They usually have large rechargeable batteries that typically offer at least 15 miles of pure electric range before the engine kicks in, although the very latest models offering up to 80 miles of all-electric driving.

They offer some of the benefits of BEVs such as the ability to run on zero-emissions for a limited period, but they still retain an internal combustion engined (ICE) cars. As a result, they're often viewed as a bit of a stepping stone.

-

Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV)

HEV stands for Hybrid Electric Vehicle, referring to cars that combine either petrol or diesel engines with an electric motor to power the vehicle. But they have a much smaller battery than an PHEV and can't be plugged in, with the battery instead charged up by the combustion engine. That's why some firms called them self-charging hybrids, much to the annoyance of many.

HEVs are use small amounts of electrical energy to produce a more fuel efficient package that improves both miles per gallon and carbon emissions compared to a regular ICE car. And because hybrids like the popular Toyota Prius are so economical, they’re commonly used by taxi and Uber drivers.

-

MHEV

Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicles use small batteries to boost the engine’s overall performance, but cannot be driven purely on electric power. The majority of new cars being launched nowadays use at least a mild hybrid system, which makes the car more fuel efficient.

-

REx

REx stands for Range Extended electric vehicles that use an electric motor as their main means of propulsion but also feature a small petrol engine to help generate electricity when the battery is depleted.

Think of it as a PHEV with the emphasis on battery power rather than a combustion engine.

-

Watts

This is the measure of power output. In the EV world it is superseded by kW due to the number of watts that are generated.

-

Kilowatt (kW)

This is the most common unit of energy for electrical energy. Basically, 1000 watts make a single kilowatt. EVs and electric car charging points are rated by their kilowatt output.

-

Kilowatt Hour (kWh)

A kilowatt hour (kWh) is the amount of energy a 100-watt object uses in an hour. kWh is a useful measurement for comparing the performance and efficiency of EVs like for like.

It's easy to get kW and kWh confused. Basically, the power of a car will be given in kW – that's how much energy it produces – while a battery size will be given in kWh – showing how long it will last.

-

Miles per kilowatt hour (MpkWh)

Alright, mpkWh doesn't exactly trip off the tongue, but this one is pretty simple to understand. Basically, a car's miles per kilowatt hour tells you how far it will go on one unit of energy, which is a good way of showing how efficient it is. It's basically a fuel economy rating for EVs. The higher the number, the better.

There is a difference in countries that use metric measurements, with tend to use kilowatt hours per 100 kilometres (kWh/100km). That doesn't just change the unit of measurement but reverse the equation: so the lower the kWh/100km rating the better.

-

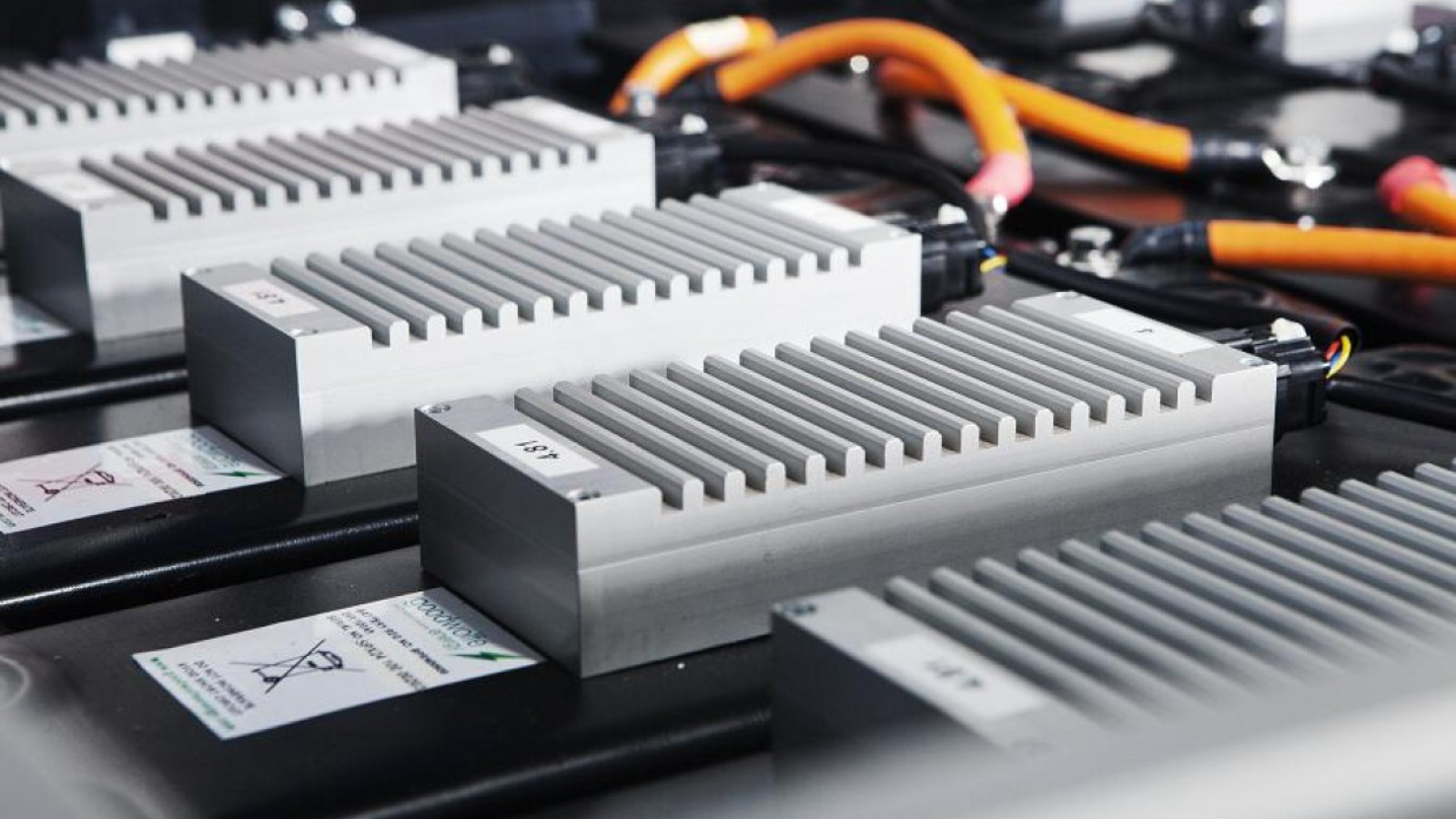

Lithium ion batteries

Due to its excellent efficiency, strong high temperature performance and high power-to-weight ratio, lithium ion batteries are perfect for EVs and used in most electric cars today. There are plenty of different chemistry types and mixes, though.

-

Type 1 connector

A type 1 socket is a five-pin plug with a clip. It's more popular on the other side of the Atlantic and among some Japanese manufacturers, but is slowly becoming less common.

-

Type 2 connector

The big hitter in Europe, Type 2 chargers feature a seven-pin plug with one flat edge and lock into charging points for better efficiency and safety.

-

Combined Charging System (CCS)

This is the standard EU connector type when it comes to fast charging, which combines a three-pin Type 2 AC connector with a two-pin DC connector.

-

CHAdeMO

Often used for rapid charging devices, CHAdeMO is certainly easier to plug in that it is to pronounce, thankfully. The CHAdeMO standard was more common with early EVs and is used for the Nissan Leaf, but it's fading from prominence in Europe as CCS charging becomes the industry standard.

-

Slow chargers

This refers to domestic plugs or home wallbox charging devices. Such chargers only have a small output of up to 3.6kW. Charging times are around 12+ hours, and be aware, on the slowest chargers that time could be quadrupled.

-

Fast chargers

Found in home, public and workplace locations, here we're talking about faster chargers that have a power output varying from 7-22kW. A full charge using a fast charging device will take around 4-12 hours depending on its power and how much your EV can accept.

-

Rapid chargers

This type of charger usually has its own heavy duty cable and plug which attaches to your car, with charge times around the two hour mark. Rapid chargers are more common on or near motorways, with AC devices offering up to 43kW of power, whereas DC rapid charges have an output of 50kW.

-

Ultra-rapid chargers

With charging speeds of 100kW, 150kW 250kW and even 350kW, ultra-rapid chargers are certainly quick. This type of charger is relatively new to the public network but are now popping up all over the place. That said, when you find one do check if your EV can accept such high charging speeds: very few cars on the market can actually charge at 350kW. Your car will only charge at the highest speed the car can accept, no matter how fast the charger can go.

Plug in to an ultra-rapid device though and you can replenish an EV’s battery with significant range in 20-40 minutes.

-

Vehicle-to-grid (V2G)

This ultra-smart technology effectively allows you to plug your car into the grid, and for it to either charge up when electricity is plentiful and low-priced, or return power into the grid when demand is high. That means you can charge up your car battery when energy prices are low (overnight) and then use that energy when demand is higher – reducing strain on the grid and your electricity costs.

Not all electric cars or homes are capable of it, but an increasing number are. Such clever energy management might not qualify you as the next Wolf on Wall Street, but it could net you a tidy income just for plugging your car in.

-

Official range

Prior to a car going on sale, manufacturers submit official ranges for their vehicles based on prescribed conditions. A variety of tests are used, including WLTP in Europe and EPA in the USA. Both combine lab and on-road tests to come up with a figure showing how many miles an EV will do on a full battery.

However, while this is useful for comparing capabilities of different cars, these conditions are rarely perfectly reflected in the real world. As a rule of thumb you should expect to take 10-20 per cent off the official range, with factors such as driving style and temperature making a huge difference.

-

Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP)

Deep breath: WLTP stands for the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure, a strict emissions and efficiency test, which has effectively replaced the NEDC test. Its purpose is to find out how far a car can go in the real world with one tank of fuel or one full charge, as well as looking at how much energy or fuel a new car uses. There’s also a big focus on emissions - not that tailpipe-free BEVs have to worry about that.

In the USA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) range test is the format used.

-

NEDC

Before the introduction of the WLTP (see below), new cars underwent the New European Driving Cycle, which was used to test new car engines' fuel economy and emissions output. The NEDC test was replaced for being too optimistic and typically provides more generous range figures for EVs.

-

Ultr-Low Emission Vehicle (ULEV)

The Ultra Low-Emissions Vehicle (ULEV) moniker refers to cars which have an official tailpipe carbon dioxide emission of less than 75g/km and is used by tax collectors and Congestion Charge zones.

-

Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ)

Ultra-Low Emission Zones are areas, usually in big cities, that have restrictions on what types of cars can enter them in a bid to reduce emissions.

In the UK, London now has an Ultra Low Emission Zone charge that runs alongside the Congestion Charge Zone (CCZ). Older petrol cars which do not meet Euro 4 emission standards or diesel cars which does not meet Euro 6 standards are required to pay a fee for entering the zone, which is in operation 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Electric cars are exempt from the charge, because they do not produce tailpipe emissions. The ULEZ zone will be expanded in August 2023 to cover all London boroughs. It is also worth noting that Birmingham and Glasgow have similar low emission zones, and more cities are expected to jump on the bandwagon as the Government pushes to meet its net zero targets.

-

Range anxiety

This is the term for the unwanted sweat-inducing fear that EV drivers get when their EV is running low on charge. Thanks to improvements in both the range of electric cars and improvements to the charging network, EV drivers are finding this is becoming less of a problem. The current rise in the uptake of EVs has - reasonably - led to calls for an even faster rollout of more chargers.

The truth is that, with modern EVs offering ever-longer ranges, range anxiety isn't really a thing any more. The problems lie with the charging networks, with most nerves caused by a fear a driver won't be able to top up their battery easily. So perhaps charging anxiety would be a better term?

-

Regenerative braking

This is where energy created under braking is harnessed and then used to charge the batteries while on the move.

Modern electric cars are fitted with this feature, with many allowing the driver to set the effectiveness of the regenerative brakes. In fact, the force of the regenerative system - instigated when lifting of the accelerator - is so strong that you don’t even need to press the actual brake pedal.